Damp Documents

The night of the flood, I wasn’t sleeping. The water was too loud. It felt like the night before something big, like something somewhere was being destroyed. My senses widened and then shrunk, the clouds cracking around time. A harshness comes with unexpected excess. If I fully heard all the harshness in the world, I would not survive.

In the morning, I received a text from my sister that my parents’ basement was a little soggy; then, another text from my mom asking me to come over to help. She never asks for help, so it must’ve been more than soggy. Their basement usually leaks during rain storms around the walls in tiny pools that collect to the basement drain. Was “soggy” a placard to place over the damage for now, a word before the panic? Was it a misunderstanding of the reality? I would soon learn my parents’ basement had become the depth of a fish tank overnight, while they slept, ruining anything within twelve inches of the ground to the wall.

After scrolling through social media videos of cars underwater in other parts of the city, I left work and headed over. The visual reality of the drive felt familiar, a surreal normal. It wasn’t clear yet how that night had given us the biggest flood in St. Louis since the 1800s. The city has different levels, some neighborhoods at the tops of hills, and others in lower pits. There was an unevenness to the disaster’s form. The highway bent around the green grass, the green signs of location.

The drain at the bottom of the outdoor steps to the basement had clogged, allowing every gush to pour in through the faulty crack at the bottom of the old door. One sliver of space opens between materials and the unimaginable is allowed.

When I walked in, my mom was standing over the dining room table looking at old photos. They were drying in a checkered form all over the peacock tablecloth, pictures mainly from my dad’s life. He doesn’t even know who some of these people are, she said. She was shaking her head. She was crying. I had to throw away your old toys and papers, she said.

Everything in the basement, since I was a kid, had stood still until now. Objects and furniture had rarely moved or needed rearranging. The basement contents, baby dolls or old camping gear, stayed in milk crates and plastic sets of drawers as we became older, changing. I imagine the sound the basement hears: my parents padding and creaking around the wood floors above, with all their daughters long moved out. Below: the roots of memory. In recent years, my dad lost full mobility on the right side of his body, yet his guitar and table with songbooks still sit in the basement’s corner. He used to go down there to play music alone; his moments of meditative peace, notes and words.

I walked down the wooden stairs scrawled in my childhood pencil messages. Once in the basement, I noticed the unfinished floor was streaked in mud and fading water. Wrinkled papers were set up flapping around fans and stacked on a table, which my two sisters were standing over with their heads down, thinking.

What are the documents of a childhood? Newspaper clippings of acting camp, concert band programs, bat mitzvah pamphlets and speeches, fliers for school plays, all carefully slipped inside clear plastic pockets in a curated binder, now dipped in rain. A scrappy collection of kids’ paintings and report cards and homework assignments and drawings made on boring afternoons, all kept for decades. Some parents would’ve thrown this stuff away, I said.

These jagged stacks of experience were never meant to endure. My life. Without an air-tight storage method, on the bottom shelf of the closet, the water pushed its way into the cardboard box. My mom archived our lives in this simple, messy way that feels true to those times, to us. Growing up with my kind and creative parents, we were modest in indulgences and the toys we were allowed to have, but we truly had everything.

You were so much fun when you were kids. You were so talented. My mom was in mourning.

I realized I was crying, too. I tried to muffle my tears but they kept sliding off my vision.

Mom, we are still alive!

This statement is only partially true. The children of ourselves will never return.

Laurie Anderson once said that the death of a person is the release of love. What about the death of objects? Do objects release love, too?

The painted drawings bled. Pressed against other pages in water, they created duplicates of their image, like printmaking, or the stain of memory. I opened a book someone made: washable paint, a kid-friendly art supply, now washing away itself. A deep color blossomed. Everything combined into one form, the page as mudslide. On the child-made book, on each side of the spine, the left page contained the source of dye, a lost drawing, and the right side contained the blotted lined paper, the words of a short story.

Writing this down now, I’m looking at a photo on my phone that I took of the book before I stuffed it into a trash bag with the rest of the rain-crushed paper. I took pictures of whatever I wanted to keep, even though I couldn’t have them in the physical world. I zoom in with my fingers on the screen, squinting at the pencil words hidden behind the resurrected cloud of ink. I decipher, like a black-out poem: “– a huge tree in M____ backyard. The tree was bigger than any other tree Windy, Elle, and Zack had ever seen. “Wow!” cried Windy. “That tree is really huge.”” At the top of the page: “Oh, ____ you don’t have a home.”

It’s clear to me now that this was my writing. The character names were the names of my best friends from elementary school, and “Windy” was a pseudonym for myself. As a kid, I wrote and drew as a constant creative practice, constructing fictional characters, becoming them. I wanted other people, other names, to explain my desires. In the cocoon space of my safe midwestern upbringing, I was allowed possibility and also boredom.

My childhood was a time before I truly knew about the world’s darkness, before it ever seemed imaginable that our bodies could get damaged and dispirited. I don’t know when it shifted for me, when fiction storytelling fled my mind. As an adult, I switched to nonfiction, reality, and never returned. Now when I write, I reconstruct what is in front of me, the visual of it, the feelings behind my eyes. It’s like a metaphor for growing up. In phony concepts of maturity, I left behind my kid-self’s abundance of making-up the world.

Another page: “At first everything was silent. ____ then a huge beam of light spread around the tree. Windy thought she was going home ____”

In the childhood text, I had written “Wendy,” but here I edited it to “Windy,” like the other page. I don’t know which spelling of my character is right or wrong.

Laurie Anderson’s documentary was advertised to be about the death of her dog, but is actually about the death of her mother, and when viewed closely, is actually about the death of her partner Lou Reed.

The lower rungs of the basement bookshelves were hit hard. These were books that were too old or unimportant or un-read to be arranged in the primary bookshelves upstairs. There are public books we show off, and then there are private books we keep underground.

I walked out to the carport where we were placing trash bags of the destroyed stuff for the haulers to come pick up the next day. In the heap, I found a bag full of my mom’s old archaeology books from when she was in grad school, now muddied. I’ve been meaning to throw those out for a long time, she said, standing by the clumps of soaked stuffed animals from the 1980s and 1990s.

These were hard-bound academic journals with different articles by archaeologists and scholars analyzing their findings and research. I flipped to an article about funeral rituals, tombs and graves, explaining the deposits of people and their things left behind. I wanted to believe that my mom must have other archaeology books somewhere else in the house. But maybe these were the only ones left. She doesn’t practice or study it anymore. Like archaeologists, we gathered the old papers and dug through them in fragile fistfulls. But maybe the objects aren’t really ours to take – they belong in the earth, the past. We unexcavate.

The verb that goes with trash is always “throw.” To “throw” away something makes trash appear as a transitory blur, passing through the air, before crashing to its end place, the dump. “Throw” also implies a repulsion, a desire to flick something off our bodies with force, instead of carefully carrying it to its destination. When I throw something away, I don’t know where it goes. The location of the object disappears from certainty, from knowledge, from my belonging; my longing.

The dining room table was stamped with the rectangles of photographed people in their homes, their lives. I found a series of my grandma Bess and her friends in North St. Louis when she was a young woman or teenager, back before she dyed her hair blonde, with a gang of fellow brunette Jewish girls with 1940s style hairdos and jackets. The photos are joyful snapshots of funny friends at the park, hanging off a sculpture, holding onto each other. I flipped the image to the back, where someone had written the names of the friends in cursive, including the word “Me.” The person documenting didn’t realize their own name would vanish from future understanding.

Do you remember your mom’s friends, Dad?

Oh, yeah. That’s Sylvie. That’s ____. _____.

I didn’t recognize my grandma as this carefree young, beautiful person. She passed away so long ago, her face as a woman in her 80s ingrained in me. In the picture with her girlfriends, childless, someone else, her expression lifting towards the corner of paper. That is her, right? I bet I could analyze the figure of the sculpture they posed with and find out which St. Louis park they were at. In the picture, she becomes a sculpture, too.

I looked over and my mom was at the table watching a YouTube video. I looked closer, and it was a video of how to salvage an American Girl Doll from water damage. My mom focused on the tiny screen with her reading glasses. The video emitted a generic stock-music song. We both hovered over the screen showing us how to unscrew the head and take out the fluffy white stuffing from the torso.

The dolls were being saved from the flood because my nieces will play with them. My mom, the thoughtful recycler. They were expensive, she said. Later, I’d enter the bathroom and see the stuffing-less bodies of the two cloth-girls hanging from the shower towel rack like wrung-out rags, deflated body sacks. Gifts from our grandma, the American Girl Dolls were the fanciest toys my sister and I owned in elementary school. Our past prized possessions, now gone through disaster, decapitation, rehab. Like the fiction story characters, I can’t remember the last time I picked up a doll and played, acting her out, pretending she was real.

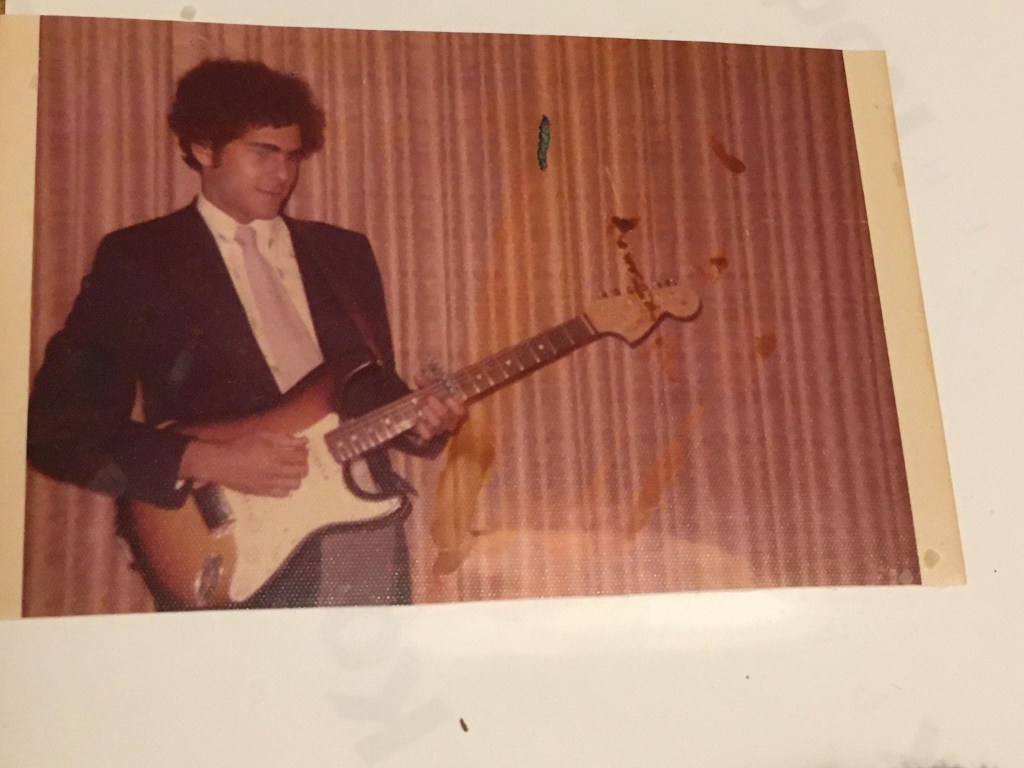

Another photo on the table: my dad playing guitar. He had this cool curly coiffed hairstyle from the 1970s. His solid-body electric guitar was on cappo 9. What song was he playing? My sisters guessed The Byrds, or “House of the Rising Sun.”

My dad’s music books and old folk music magazines were on the bottom shelf, too. They were so water-logged, they expanded and stuck to each other in an unmovable block, glued. We cried. We choked on our own flood. The sheets of paper get trashed, and we are left in their undoing with our feelings. My dad hasn’t been able to play guitar for years due to his disability. He was upstairs while we shuffled through the damage, unable to casually approach the basement like we could. He was watching the news, the weather.

This could all be a preparation for much bigger floods, bigger losses. I imagine more climate disasters coming towards the next decades of my life, like a slow build of water, leaving stains on the wall like hash marks of new heights. We will slowly become accustomed to displacement and adaptation. Some people line their basements not with books and old papers and toys, but with canned foods and alternative power sources.

Of course, throwing away entire sections of my life is preparation for some future when my parents’ house, the house I grew up in, will be sold. We will gut it of everything that it had, and we will make real graves for each other. The days of artmaking and reading books and making up lives and playing guitar will become wisps of air with no structure on which to attach.

It is terribly hard for me to confront this: the end of life, my parents getting older, the world feeling less possible. My family has a collective difficulty confronting pain. We look at our wounds and call them diminishing words (soggy!) to detract from the horror. In writing, I can try to say what is happening with deeper language as markings. My survival. In hopes we leave the earth with any documents as proof: we lived here.

In Laurie Anderson’s film, she consistently places a filter over her footage to look like a pane of glass pocked with raindrops. Like a mesh of moisture over history, looking out the wet window towards blurring memory, outside of it. The first time I watched her film, I felt like this was the most accurate portrayal of remembering I had ever seen.

In the stack, I did find one nonfiction essay I wrote as a kid: an entire explanation of every year I went to elementary school in detail, which I must have written for a fifth grade assignment before graduation. Each paragraph described each grade, my teachers and friends, class projects and school trips, inside jokes I now re-recalled. It felt like a magic trick to devour my old self in a summary, my small life.

Around the table of papers, my sisters and I decided what selected documents should be dried and kept and hope for no mold. My elementary school essay was one I chose, along with a birthday card my grandma Bess wrote me for my 14th birthday. I draped the paper on the seat of a chair by a small fan. The next week, it dried out into a wavy crisp texture, and I decided to throw the essay out anyway. I was unsure I really needed it, accumulating in the messy drawers of my apartment. It’s overwhelming to know all of these objects exist. I felt like I only needed to look at the memory once more before never seeing it again – that’s how memory usually works, anyway.

I let my old hobbies and events and imaginative thoughts become lost to me. The grief of the documents is: we don’t need them anymore. We changed. We miss each other so much.

Writing this now, I regret throwing away the essay. I wish I had kept it after all. I will never feel satisfied with these actions, our deaths.

What did it even say? For field day of my kindergarten year, it was American states themed. We were Alaska. I ate all the beef jerky.

###

Delia Rainey is a writer, educator, and musician living in St. Louis, Missouri. She is the author of the chapbook CRUMBBOOK (Bottlecap Press Features 2021). Her writing recently appears in Midwest Review, Grist Journal, and Brink. Her band is called Dubb Nubb.